Every so often, a publishing project pushes a medium as far as it can reasonably go. After that point, the conditions change. Technology shifts. Economics shift. The moment doesn’t repeat itself. David Roberts’ Egypt & Nubia belongs to one of those moments.

Art historians and bibliographers have been unusually consistent in their assessment of Roberts’ great folio projects — The Holy Land and Egypt & Nubia — describing them as the high-water mark of nineteenth-century tinted lithography because they represent the moment when technical skill, artistic vision, and publishing ambition briefly aligned.

Drawn on the Spot

Between 1838 and 1839, David Roberts traveled extensively through Egypt, Nubia, Palestine, Syria, and the Holy Land. He worked without the backing of a formal expedition, carrying letters of introduction and sketching directly on site — often outdoors, in heat, sand, and difficult conditions.

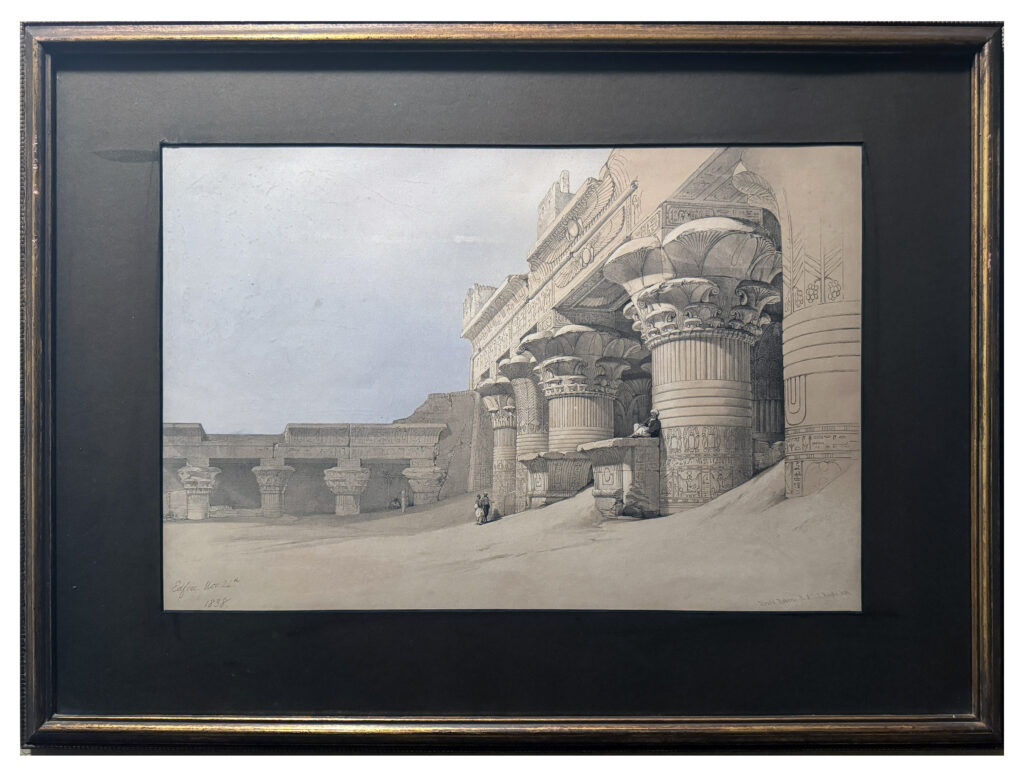

Roberts was not inventing scenes for a European audience. He was recording what he saw, then later transforming those drawings into finished compositions. His journals are full of complaints about the sun, exhaustion, insects, and time pressure, but also moments of awe. At Edfu, he writes of sitting exposed to the heat, worried he hadn’t done justice to the pronaos, even as he admits he couldn’t resist drawing it.

From Edinburgh Scene Painter to Monumental Vision

Before Egypt, Roberts had already lived several artistic lives. Born in Edinburgh to a shoemaker, he began as a house painter, then worked as a scene painter for theaters and touring productions. He painted backdrops at night, learned to construct space quickly, and absorbed the logic of stagecraft: how to guide the eye, how to suggest scale, how to place figures so architecture feels inhabited.

That background is often treated as an anecdote but it shouldn’t be. His professional history explains why Roberts’ monuments never feel static. The temples breathe, the ruins feel occupied, and human figures appear as scale markers — small, deliberate, and incidental.

By the time Egypt & Nubia began publication, Roberts was no longer an obscure artist. He was a Royal Academician and a figure of real cultural weight.

A Publishing Project on an Unusual Scale

Egypt & Nubia was published in London between 1846 and 1849 by F. G. Moon, issued by subscription in parts. It was among the most expensive illustrated publishing projects of its time, ultimately supported by roughly 400 subscribers.

Queen Victoria was subscriber number one.

This detil signals how Robert’s works were understood at the moment of their release — as prestige objects, meant for collectors, libraries, and institutions rather than casual buyers. Subscribers committed in advance, receiving plates over time before binding them into volumes.

The full project eventually comprised around 250 lithographs, with historical texts by William Brockedon and George Croly.

How These Lithographs Were Made

The images were lithographed by Louis Haghe, working from Roberts’ drawings and finished watercolors.

Most plates were printed using a small number of stones: a key stone for the drawing, plus one or two tint stones — often pale blue for sky and a neutral or warm tone for architecture and ground. The color was not added later as traditional hand-coloring, but built into the printing process itself.

Roberts’ working method — transparent washes laid over pencil outlines — proved unusually well suited to lithography. Instead of fighting the medium, his drawings translated cleanly and faithfully, allowing Haghe to produce prints that retain both architectural clarity and atmospheric softness.

The Plates in This Group

The four works I’ve been living with come from Egypt & Nubia and date to the heart of the project:

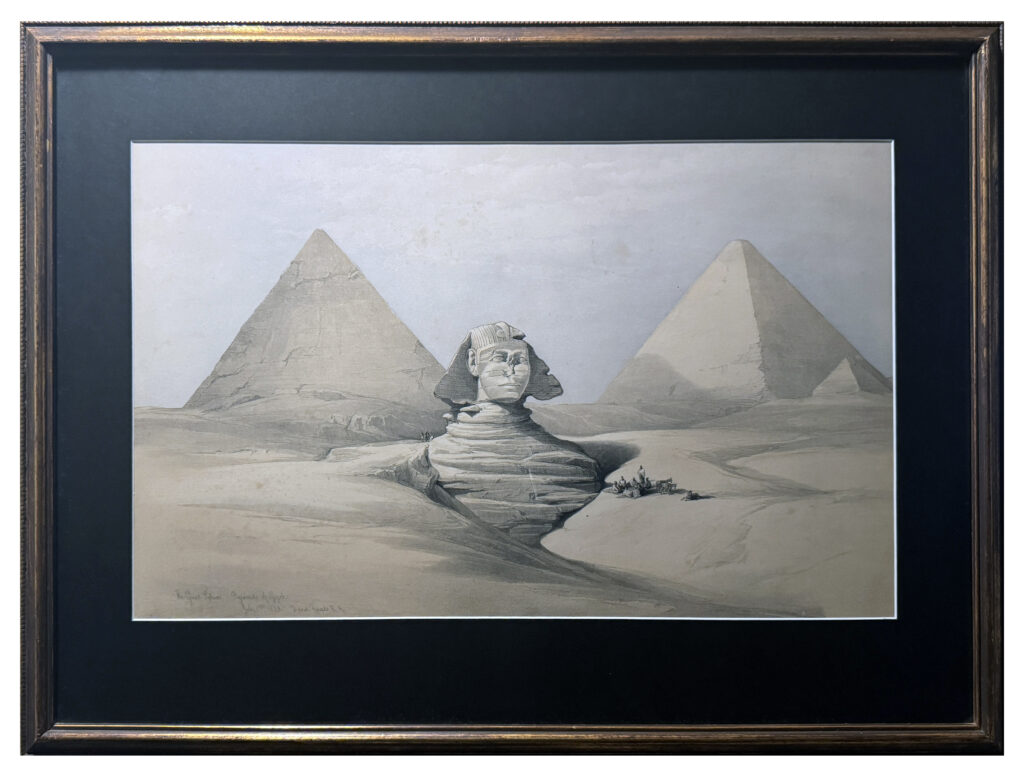

- The Great Sphinx, Pyramids of Gizeh

- Edfou

- Statues of Memnon at Thebes, during the Inundation

- Grand Portico of the Temple of Philae, Nubia

Seen together, they show the full range of what Roberts achieved: monumental scale without bombast, meticulous architecture softened by light and distanced.

Why They Still Matter

Photography arrived not long after these volumes were completed. Publishing economics changed. The skill required to coordinate artists, lithographers, printers, and colorists at this level became impractical.

That’s why these works don’t feel like a step along the way. They feel like a culmination.

These prints represent a brief moment when lithography could rival painting as a medium of record and beauty — when a printed image could be both technically exacting and emotionally resonant. Once that moment passed, it didn’t come back.

Sources & Further Reading

- New Statesman, David Roberts: Victorian visions of the Holy Land, Michael Prodger

https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/art-design/2022/06/david-roberts-painter-the-holy-land-syria-idumea-arabia-egypt-and-nubia - Fleming Collection, David Roberts biography

https://artuk.org/discover/artists/roberts-david-17961864 - Royal Academy, Egypt and Nubia from Drawings Made on the Spot by David Roberts RA

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/book/egypt-and-nubia-from-drawings-made-on-the-spot-by-david-roberts-r-a-with - Metropolitan Museum of Art, David Roberts works and context

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search#!?artist=Roberts,%20David - Abbey, Travel in Aquatint and Lithography, entry on Egypt & Nubia

Leave a Reply