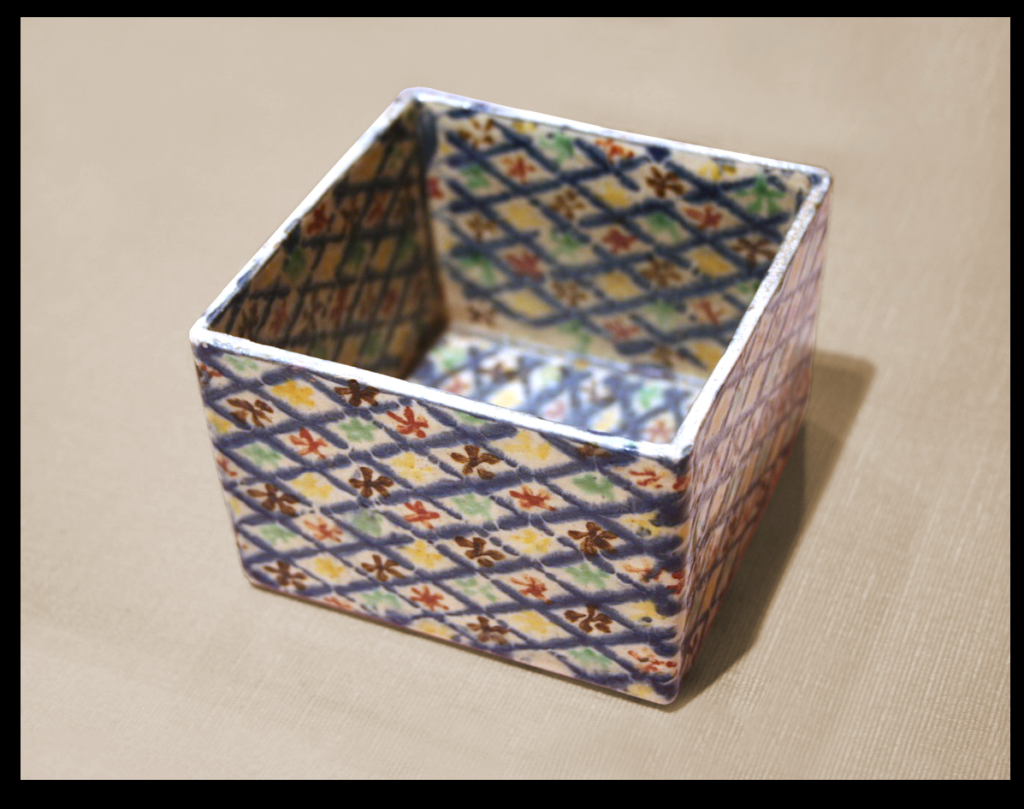

Here are three Japanese mukōzuke that feel almost contradictory. Square forms are already a quiet rebellion in Japanese ceramics, where curves and soft silhouettes tend to rule. These pieces lean into geometry. The exteriors are bold, saturated in iron red and confident gold. Inside, everything shifts. The glaze turns pale and luminous, softening the severity of the form.

Produced by a Kyoto studio in the early twentieth century, likely between the late Meiji and early Shōwa periods, all three pieces are signed on the base with a bold, graphic mark. The signature is clear and intentional, though the maker remains unidentified. Whoever made them wanted their work to be seen, even if their name has faded.

The decoration is classic Kinran-de: deep red enamel with finely brushed gilt bamboo, grasses, and a stylized floral crest. Because of this palette, pieces like these are often associated with Kutani ware. It’s an understandable assumption. But the lineage begins in Kyoto, with the Eiraku tradition, which later informed and shaped Kutani production.

Kyoto in the 1920s was a period of experimentation. Studios were steeped in tradition yet increasingly aware of modern taste and international markets. Export wares at this level weren’t factory products. They were made deliberately, often in small numbers, for buyers who wanted something recognizably Japanese but not bound by ceremonial use. The square form here feels very much of that moment — architectural, confident, and forward-looking.

Square vessels had appeared in Kyoto ceramics long before this period. Early masters embraced geometry as a way to challenge convention, and twentieth-century potters understood that history well. Rather than copying earlier forms, they borrowed the idea of the square as a signal of refinement and experimentation. True square interiors are technically difficult to glaze and fire, which helps explain their relative scarcity across all periods.

Formally, these pieces align with mukōzuke, small presentation dishes used in Japanese dining. Their straight walls, fully square interiors, and pale blue glaze feel oriented toward display rather than drinking. At the same time, they can function comfortably as sake cups. That kind of flexibility was common in early export wares, which were designed to be admired and used creatively rather than confined to a single role.

What interests me most is how comfortably these pieces sit in between — between form and function, between eras. They read as bold and modern, yet they clearly draw from the work of Japan’s finest craftsmen. At the same time, they feel worldly. It’s easy to imagine them holding sashimi in Kyoto, or champagne at the opening of the Chrysler Building in New York.

The modern wasn’t invented all at once. It was arrived at slowly, rediscovered again and again by makers willing to look backward and forward at the same time. These pieces feel like part of that ongoing conversation.

Sources:

https://www.gotheborg.com/glossary/kinrande.shtml

https://musubikiln.com/blogs/journal/what-is-akae-kinrande-eiraku-style

Leave a Reply