The Acoma Plateau, often called Sky City, is widely recognized as the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States. For more than a thousand years, Acoma potters have shaped clay gathered from the surrounding mesas into vessels that are both functional and astonishingly refined. Long before pottery was made for collectors, it was made for daily life, trade, and survival—and that continuity still shows in the work today.

Acoma pottery is known for its extraordinary delicacy. The walls of well-made jars are remarkably thin and light, the result of careful hand-coiling, scraping, and polishing rather than the use of a wheel. Decoration is equally demanding. Designs are painted freehand, traditionally using natural pigments and brushes made from chewed yucca or grasses, allowing for lines so fine they appear almost etched. Black-on-white geometric patterns—stars, lightning, rain, and cloud forms—are not decorative filler, but visual languages passed through generations.

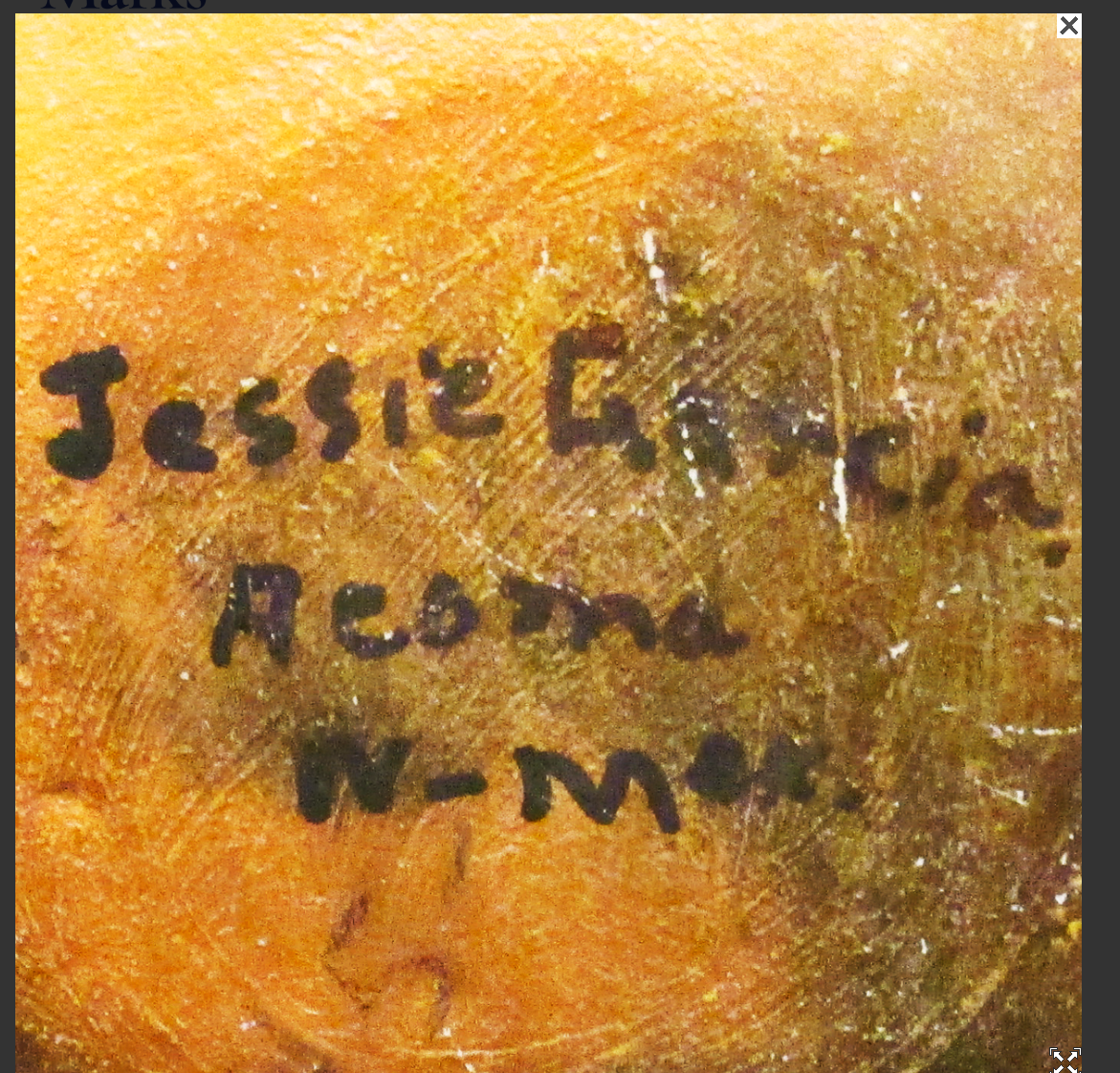

Pottery making at Acoma has long been a communal and intergenerational practice. In some cases, more than one artist contributes to a single piece. When two names or sets of initials appear on a pot, it typically indicates that one person formed the vessel while another applied the decoration. This division of labor reflects how knowledge and skill were traditionally shared, particularly within families.

While neighboring pueblos such as Laguna share related histories and visual traditions, collaborations between Acoma and Laguna potters are uncommon. Each pueblo maintains its own clay sources, methods, and design emphases, and artists usually work within those boundaries. When a pot bears references to both pueblos, it stands out as unusual and worthy of closer study.

The three pots discussed here exemplify these traditions. All are finely made, thin-walled, and undamaged—no small thing given how fragile well-crafted Acoma pottery can be. Each is signed, but in ways that raise thoughtful questions rather than provide easy answers. Common family names appear, and in one case, dual initials suggest collaboration, yet there is no definitive record linking the marks to specific, documented individuals. This is not unusual. Pueblo pottery histories are often preserved through oral tradition, family teaching, and lived practice rather than written records.

What is clear is the quality of the work itself. These pots were made by skilled hands, using methods refined over centuries. Even without full attribution, they sit squarely within a living tradition that values precision, restraint, and deep respect for material.

Leave a Reply