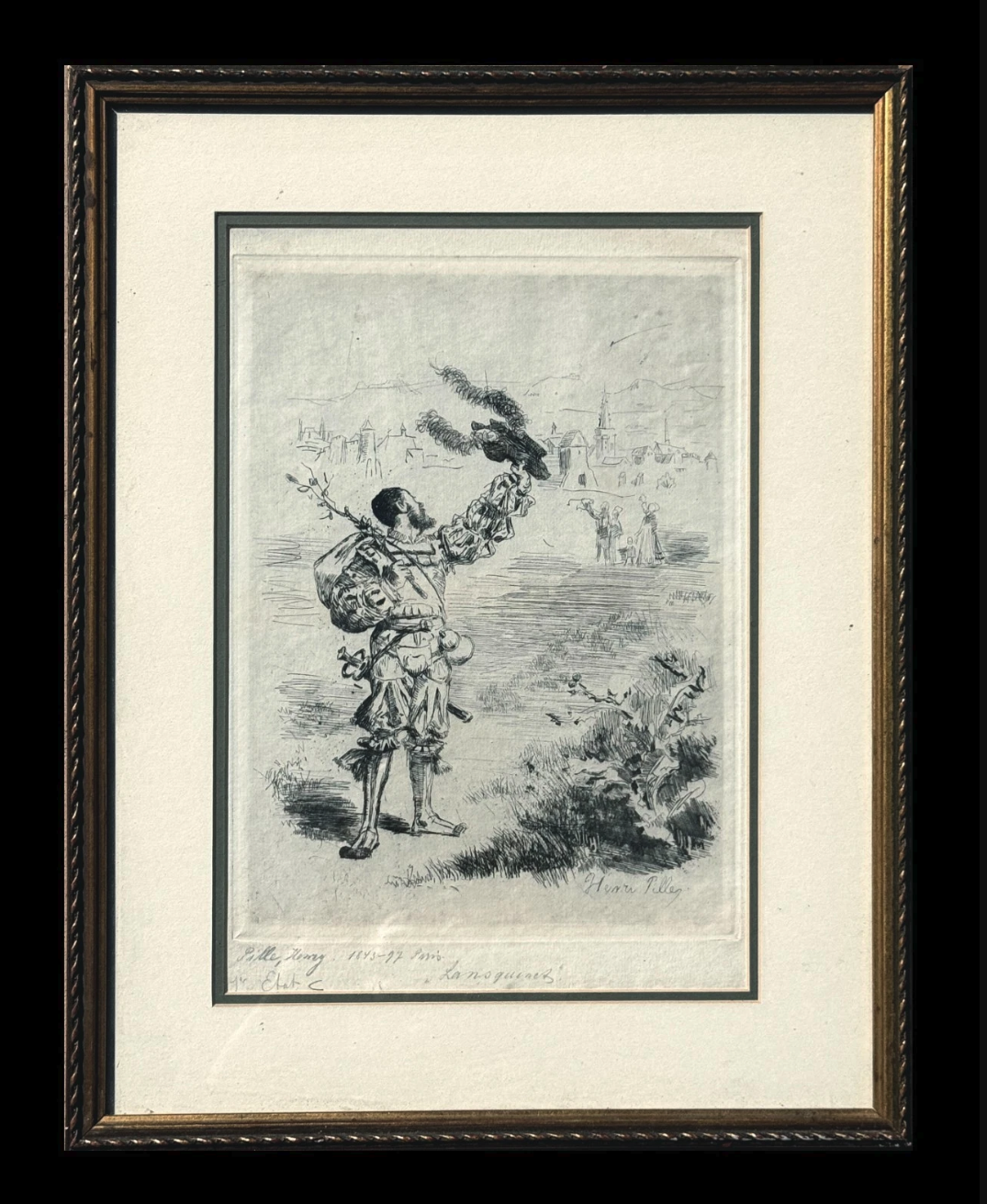

I keep coming back to this Henri Pille etching because it exposes something uncomfortable about how value actually works.

I bought this etching convinced I was looking at an Old Master. The line is expressive and assured, the figures hold weight, the shadows feel built. If you squint, the hand isn’t far from Rembrandt—not in ambition, but in confidence and control. Someone who knows exactly where the line needs to go, and just puts it there.

And yet here it sits in my ebay store. Nine views. One watcher. Listed at $125.

That gap—between what the work is and what the market is willing to do with it—is the story.

Henri Pille worked in Montmartre at exactly the right place and time, surrounded by artists whose work would only be fully valued long after their deaths. Many of them would later define entire movements, reshape art history, and break price records—often posthumously. Pille wasn’t marginal in his own time. He showed at the Salon, won medals, illustrated major literary works, helped shape Le Chat Noir, and earned the Legion of Honour. Van Gogh admired him. That alone should give anyone pause.

But admiration doesn’t always translate to success or value in the eyes of the market.

Van Gogh grouped Pille with artists like Paul Gavarni, Henry Monnier, Honoré Daumier, and Gustave Doré—a revealing list, not because their markets align, but because they don’t.

Here’s what that divergence looks like now:

- Gavarni sits higher than people often assume. His lithographs and drawings commonly land in the high hundreds, with desirable works—like his self-portrait holding a cigarette—selling around $800 to $1,200. He’s respected, recognizable, and quietly collectible.

- Monnier is split almost cleanly by medium. His etched works often trade in the low hundreds, but his color lithographs—especially the satirical figures from Modes et Ridicules—can sell for thousands. His Print Dealer (c. 1820–1830) lives in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a reminder that institutional importance and market value don’t always move together.

- Daumier occupies a different category altogether. Prolific, heavily studied, and canonized early, his lifetime lithographs routinely sell in the several-thousand-dollar range, with strong examples reaching $6,000 or more. Here, scholarship, museums, and the market are in rare agreement.

- Doré is similarly bifurcated, though in a different way. His reputation rests largely on illustration—Don Quixote, Dante’s Inferno, the Bible—but first-state etchings and strong impressions can command $4,000 to $5,000, even when they originate as book plates.

Same century. Same city. Overlapping circles.

Wildly different outcomes—often determined less by ability than by how easily an artist’s work fits into a story collectors already recognize.

Pille sits closer to Gavarni and Monnier in market terms, despite credentials that suggest he could just as easily be read upward. His problem isn’t quality. It’s narrative. He didn’t found a movement, didn’t become shorthand for a style, didn’t leave behind a myth that dealers could reliably trade on for a century. He made excellent work, consistently, in a crowded room.

That’s the uncomfortable truth: markets don’t price skill. They price stories people already know how to tell.

So when I look at this etching—Landsknecht, a first-state impression, beautifully printed, confidently drawn—I don’t see a $125 object. I see a work stranded between categories. Too serious to be decorative. Too obscure to be canonical.

And maybe that’s the real appeal.

Because if you care about drawing, about the discipline of line, about Montmartre before it hardened into legend, this is exactly the kind of piece that rewards attention. The market may never catch up—or it may, quietly, decades from now, when someone else realizes what they’ve been holding all along.

Sources

https://cuberis.com/doredemo/#timeline-bible

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/357895

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henri_Pille

https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let333/letter.html#translation

Leave a Reply